Nana hated goodbyes, but she knew sometimes they were necessary. When you had to leave her, she wouldn’t let you do so easily. She’d insist on walking you to the door. She’d stand in the hall and give you a long, sincere hug, and with a sad tremble in her voice, she’d say goodbye—several times. She’d watch with longing as you walked to your car, started the engine, and reversed out of the drive. Sun, rain, snow, or gale-force winds, she’d stand outside waving until your vehicle was out of sight (often waving for a few seconds longer, just in case).

Nana hated goodbyes, but she knew they were necessary. She didn’t enjoy them, but she understood people had places to be, things to do, and other people to see. Nana would always be the first person to tell you to follow your dreams and get on with your life.

Nana hated goodbyes, and I was to give her a eulogy, her last goodbye. When Nana died, it hit me hard. She was my go-to person. When I felt scared, lost, or heartbroken, all I had to do was call, and she’d tell me everything would be OK.

————————-

Nana had strong and simple beliefs, she had a clear understanding of what was right and wrong, but she wasn’t old-fashioned. She enjoyed learning new things and wasn’t afraid of the world changing around her. I bought her an iPad to keep her in touch with family, and she picked it up quickly. She enjoyed showing me old videos of the speedway she watched as a child and played the songs she would dance to as a young adult. With every song and video, there was a story she was eager to tell.

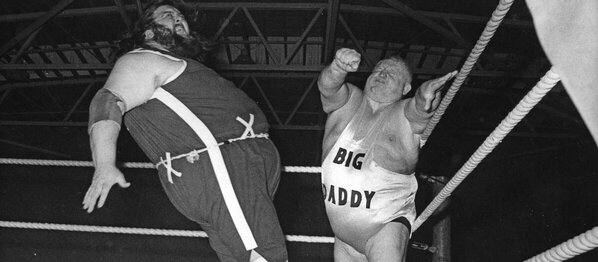

One of my first memories of Nana was going to watch British wrestling at the Corn Exchange. I was 7 or 8 at the time and was excited and overwhelmed by it all. Everyone knew Nana as soft and kind, well-mannered, and exceedingly courteous. Those wrestling events were filled with masculine aggression, tribal chanting, and many swear words I heard for the first time — most of which were coming from Nana. She’d cheer and chant for the caped hero, Big Daddy, geer and hurl abuse at Rollerball Rocco, and plead for someone to violently unmask poor Kendo Nagasaki. Rather than being intimidated, I felt privileged to see this side of her that most never knew of. I spent as much time looking up at Nana, as I did watching the ageing men brawling in their capes and masks.

Nana kept every letter and heartfelt note she ever received and kept them in the top draw of her bedroom chest. If you wrote anything more than your name in a christmas card, it usually made the draw. This was the priority draw, the quickest and easiest to get to by far. Rather than store her underwear and items she needed to get to every day, this draw was exclusively for the words she’d received from people she loved.

She kept every painting, drawing, and piece of pottery her children and grandchildren ever made. Our family is very short on celebrated artists and no matter how hideous the creation, once presented to her it would be on prominent display along the shelves and cupboard tops of her home. For her these garish and bizarre objects were perfect, proudly displayed like a piece of fine art or historic treasure.

————————-

For many, Nana was a voice of comfort. She was wise and loving, kind and consistent. The love she gave the people closest to her was unconditional. I shared with her many secrets, moments of joy and excitement, and as many moments of pain and heartbreak. She was my go-to person. The first person I’d call with good and bad news. She was often the only person I would call in my darkest moments.

The first time I began having panic attacks, I was scared and didn’t know what was happening. I genuinely believed I was going crazy, overwhelmed by a sense of doom. I researched it, spoke to doctors, tried to follow all the good advice I could get, but I had deep distrust in everything, even the words I repeated to myself. She was the one who could still always calm me. She didn’t have any life-changing insight into anxiety, but when she told me everything was going to be OK, I knew it was.

————————-

The days after her death, I couldn’t accept she was gone. I couldn’t get my head around her not being there anymore. I tried to face it head-on, but it instantly filled me with dread. Someone then told me Nana was with them. They said she’d been standing behind them when they performed on stage the night before. Ever since she died, she’d been there watching over them. Rather than comfort me, it annoyed me. It was nonsense. When you’re gone, you’re gone. This is something people tell themselves to hide from pain and grief. It was not what I wanted to hear or what I wanted to do.

The night before Nana’s funeral, I babysat my sister’s two-year-old daughter, Rosa. Like me, Rosa was the first of her generation in our family. We’d already grown a quick connection, and I felt that unconditional love from the moment I first saw her. I was anxious about having to read the eulogy the next day and welcomed the distraction of keeping her entertained. As I showed Rosa old videos of British wrestlers and told her stories about the eccentric characters from Catweazle to Giant Haystacks, I saw her staring up at me rather than watching these absurdly dressed performers throwing each other around the ring. And that’s when something clicked.

Nana never liked goodbyes. When I gave the eulogy, it wasn’t time to say goodbye, and I felt her there with me. Not a ghostly figure or a voice in my head, but I had started to feel a piece of her was a piece of me.

I started to feel her as I shared my passions and told stories about the things I love. I started to feel her as I treasure the moments and objects given to me with love. And while I was still a little scared that I could no longer call if things got to much, I started to understand that it was now my turn to be someone’s go-to person. It was my turn to answer the call whenever they felt scared, lost or heartbroken.

The eulogy wasn’t about saying goodbye. It was a moment when we didn’t have a more important place to be, thing to do, or person to see. It was to remind everyone, and myself, of who she was and what she taught us. And to tell those who needed to hear it that everything was going to be OK.