Writing a feature-length screenplay can be an incredibly demanding and exhausting experience. Why would you want to put time and effort into writing a script treatment? A good treatment is essential if you have a stellar idea to turn into a feature film or a completed script you’d like to get made.

For a work-in-progress, a treatment gives a structure to hold all your ideas, moments, and plots together, allowing you to write with greater confidence, efficiency, and motivation. If you have that polished script ready to send, a treatment will be its calling card. Every feature script I’ve personally written has either started by first planning it with a treatment, or it’s become my chief sales document to help me pitch it to readers.

What is a treatment?

A treatment is a document which summarizes and pitches the story intended to be dramatized for a film or television.

It is a way to explore the storylines, characters, and plots and get a clearer idea of how it all ties together. The economy of a good treatment helps you quickly see the bigger picture and overall structure of your story, allowing you to uncover potential flaws and weak points. It also helps you better understand your characters and their unique desires and struggles and experiment with how all your storylines are sewn together.

If you already know your story in intricate detail or have a quality draft on the page, a well-written treatment can become the calling card for the script. It is an excellent format to pitch your film idea early and seduce others to read, fund, and even produce your project.

A treatment is a narrative-prose telling of a screenplay. There is no set length or format, but it should lay out the story arc and subplots. It should be concise and economical in its language, giving an easy-to-follow account of the full story.

The uses of a treatment

Pre-writing

If you’re using a treatment to test out an idea, then you should write it without worrying about contradictions or flaws at this stage. Write it on the page and let it flow. Like screenwriting, the treatment itself will need to be drafted and redrafted. The time and effort you spend working on it will pay off 10-fold when you sit down to write, having a solid structure and story arc which will keep you organised and on track.

Pitching ideas

If you’re writing a treatment to pitch your idea, you must bear the reader in mind. You still want this document to tell the story in a somewhat matter-of-fact and economical way, but you may want to add something to express the tone and style of the end script. The aim is to give the reader a clear understanding of your story, it must be easy to follow and understand.

How long is a treatment?

I have seen examples 1 page long and others 20+ pages long. It can vary but is usually from 3 – 15 pages. It is advised to keep it between 5 and 10 pages as studies have shown in the industry they average between these numbers.

How to structure a treatment

There is no set structure or industry-standard format for how a treatment needs to be. You can be creative and playful, but it should certainly be centred around telling the story in a clear and easy-to-follow manner. Even when you are using it to pitch your project, I would avoid adding too much flair or styling in the way you tell the story and focus on covering all the core details and laying out the plot lines.

You can break it down as follows:

- Title

- Logline

- Characters

- Story

- Concept

Title

Titles are important, it’s the first impression most films make but don’t overthink it at an early stage. It can become an obsession to find the perfect title for your project, but many films won’t find their final title until well into production (or even after it). If you don’t yet have a title, give it a ‘working title’ which is original and sets the right tone.

Logline

This needs to be a sentence or short, punchy paragraph which summarizes your story. This is less necessary when using a treatment to plan a first draft, but writing it even at this early stage is certainly beneficial.

The logline is often the first thing I will do, and I’ll put a lot of thought and effort into creating one I’m happy with. It’s easier said than done, but focusing on telling your story in one sentence can create that crucial first building block.

If you just can’t nail the tagline at this early stage, one way of cheating it is to use other film comparisons. E.g. ‘It’s a classic Western, set in space’ – Star Wars.

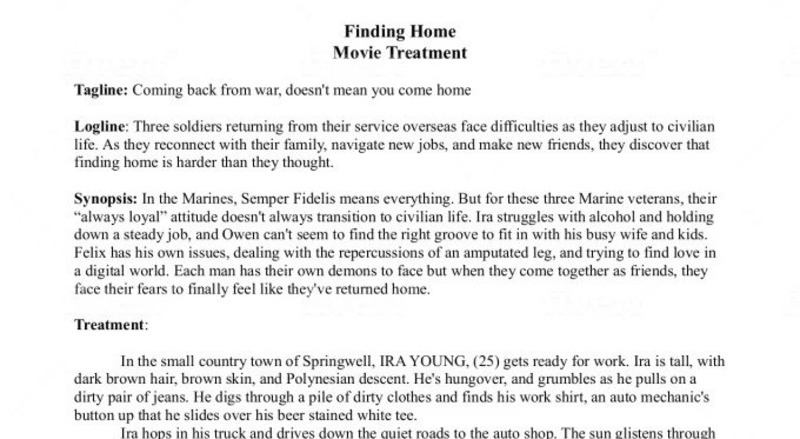

Characters

You may feel it’s better to introduce a section on your characters before you tell your story and use it as an introduction. There’s no right or wrong way to do it, and it can depend on the story and how you feel it’s best told.

You should give out a lot of character information when writing the story section, especially in the first act, and that’s important. You want to get into the story as soon as possible.

Writing the character breakdowns after the story section allows you to detach your thinking from the events of the story and just focus on who the characters are. Here, you want to cover their present (age, looks, personality traits), their past (major events and circumstances which have shaped who they are), and their future (what they want, what they need, and what stands in their way).

Try to keep this brief, down to a paragraph for each major character.

Story

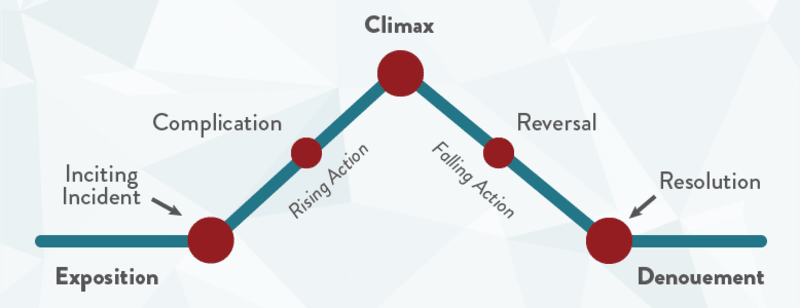

The story section can be broken down into acts or even scenes. I like to start by planning my story in 5 acts, like an extended synopsis, and later expand this into something closer to a scene-by-scene outline.

As this is the most important part of the treatment, I slowly build up my story, starting with the logline. Once you’re happy with your logline, telling your story in 1 sentence, you can then expand it to telling your story in three sentences:

- Set up

- Conflict

- Conclusion

I will try to be economical and rewrite those sentences within 25 words each. Again, it’s not an easy task and can take a lot of time and brainstorming, but I know this method has a payoff. From there, I’ll expand it to 5 sentences:

- Introduction (set up of characters/world)

- Inciting incident (the event that kickstarts the story)

- Highetening incident (the event which raises the stakes)

- Concluding incident (the main event of the story)

- Catharsis (the resolution of the story)

When you are happy with the 5 sentences and how they flow together, you can expand each sentence to a paragraph or more.

Working through this technique will give you those 5 crucial beats/acts that will become my story’s backbone. As you expand, adding in all the events and details, you can do so knowing your story arc will hold everything together.

Concept

You only need to add a small section on concept or style when writing a treatment for someone else to read. You should keep it brief and only put in notes on major style, concept, and tone ideas.

The tone and concept should already be somewhat clear by this stage, so it’s best not to overwrite this section. If you are writing a treatment to send to a director or producer who knows the movie will be directed by someone other than you, too many styling, technical, or production notes can even be off-putting, whereas a clear and strong storyline without too many production notes, can be seen as an exciting canvas to work on.

What’s the difference between a synopsis and a treatment?

There are many documents that serve different purposes for a screenwriter, depending on your level and how far along you are with your script.

A film synopsis is written before or after the screenplay, and it can be used for pre-planning and/or pitching to financiers and production companies. It’s usually a 500 – 1000 word walkthrough of your film.

You should think of treatment as a written pitch detailing every aspect of your story, not just the story.

Nailing the ‘perfect’ treatment

There is no perfect treatment, just as there is no such thing as a perfect script. A treatment is usually seen and understood as an early document, so it’s not expected to be extremely well-polished.

Your starting treatment may look nothing like the final draft, but using it to rework your story will play a crucial role in development. Its key function is to get you conscious of the overall story arc and what impact every moment has on the shape and flow of your screenplay.

As a pitching document, it is most commonly used to sell a film idea at a very early stage, often looking for funding and support before a first draft is even complete. Its job here is not to tell a perfectly tuned story but to give quick, easy access to the story you are trying to tell.

Other documents screenwriters may need

It’s easy to get confused with all the different types of supporting documents you might hear about. Here are some of the most common ones and what they are best used for:

- Tagline: A very short and catchy phrase, used as a teaser for a movie (e.g. ‘In space, no one can hear you scream’ – Alien). Usually found on marketing material, such as posters.

- Logline: A sentence, or very short paragraph, describing the story. Unlike a tagline, the logline should be more descriptive. (e.g. “After a simple jewellery heist goes wrong, the surviving criminals begin to suspect that one of them is a police informant.” – Reservoir Dogs). It’s a great way of giving a quick power pitch when the time/opportunity is brief.

- Plot summary: A more detailed telling of the story, usually around 1-3 paragraphs in length. It should cover the major events and story arc. This is a great format for pitching your story in a production meeting.

- Synopsis: A more in-depth story telling, including some information on the characters and their motivations. As well as laying out the beats of the main story, it should also cover major subplots. This is usually a one-page document and a great accompaniment when sending your screenplay to an agent or production company.

- Outline: A scene-by-scene breakdown of a screenplay, describing the key events and moments of each scene, in order. As well as telling the story, it also gives insight into the pace and production of the movie. It’s a good way to introduce your script to a director or production team.

- Pitch: All of the above can be used to pitch a screenwriter’s project, but when we say a ‘pitch document’ we usually refer to a more detailed format with a very concise telling of the story, including technical and production details.

- Bible: A bible is suited to TV series. It will focus on the world’s rules and analyse the characters, their background, and motivations. As well as telling the initial story and its many storylines, it can also suggest future and alternative storylines and show development potential.

It’s useful to understand the above and when they are best used. A treatment tends to borrow different elements from these documents, depending on what you will use it for.